New Dimensions for Dementia

November 2022

How can we design better buildings for the future of elderly care together?

Senior citizens make up the largest patient group in our hospitals. Currently, around 40% of healthcare costs are spent on seniors aged 65 and older. Moreover, when seniors are hospitalized, the average length of stay is significantly longer (10 days) with a high risk of functional decline that could prevent them from returning home. Therefore, we need to focus on everything that could potentially improve the recovery of senior citizens, particularly those with dementia. This includes the physical care environment.

Space affects how we think, work, move and interact. Thus, space also affects output, quality and efficiency—all of which are decisive in healthcare. Care and architecture meet in physical space: the right balance can improve care processes and yield greater efficiency and effectiveness. And that ultimately saves time—time that can benefit the elderly patient by allowing for more personalized care.

Seniors, dementia and the numbers

By 2040, a quarter of the Dutch population will be over the age of 65. It is estimated that by that time our country will be home to half a million people with dementia, most of them elderly. In hospitals, people over 65 are by far the largest patient group. In 2012, a total of over 4.3 million people were hospitalized, and 36.7% of them were 65+. The average hospital stay for people 75 and older is 22.5 days (compared to the standard 10 days). About 40% of healthcare costs are spent on seniors, a percentage that will continue to rise in the coming years.

Thinking together

Given the numbers and recent developments (e.g., rising costs and quality of care), it’s time for healthcare professionals, institutions and architects to start thinking together in order to better meet the needs of elderly clients, both in hospitals and nursing homes. We seemed to gain a lot of momentum when Carin Gaemers and Hugo Borst presented their manifesto “Sharp on Senior Care” in 2017. But have we developed new knowledge that can contribute to senior well-being since then? Have we learned anything about how we can better support care processes through spatial solutions that help free up time for clients? The answer is yes, but we still have a long way to go.

More research, better design

Wiegerinck has been researching the relationship between the built environment and dementia care for years. All of this study and research constantly yields new insights, and this knowledge nourishes our design process.

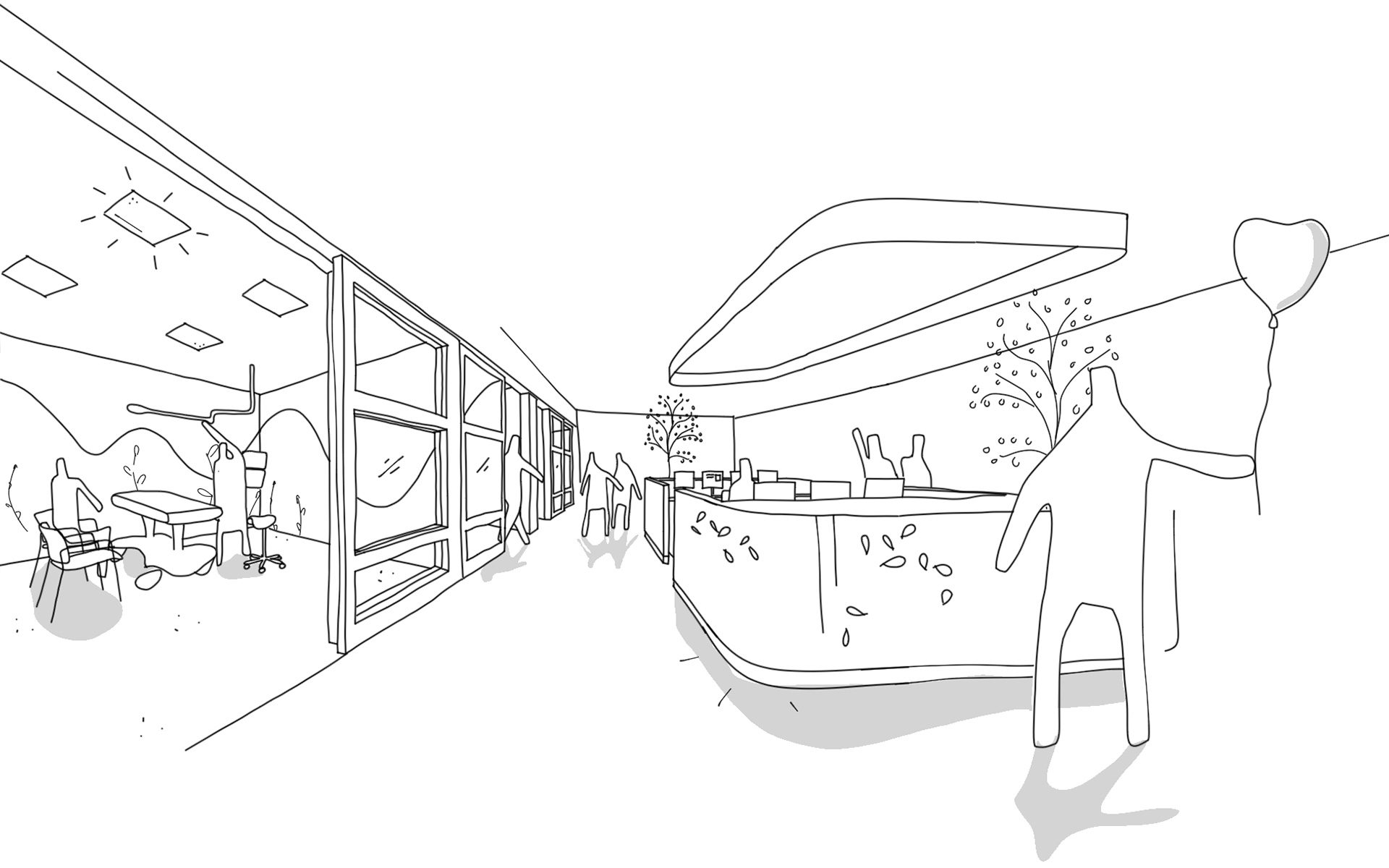

Seniors in the Hospital – Space and Differentiation

As we age, our vision and hearing decline, along with our mobility, perceptual ability, and general physical condition. With this in mind, we need to properly visualize the journey through the hospital (i.e., the “patient journey”) and observe which changes are actually improvements, across all departments. An elderly patient’s visit begins when they arrive at the hospital. But how do they and those accompanying them experience the Kiss & Ride area? What stress factors does their companion experience when parking the car and finding a wheelchair? Is there a safe place for the vulnerable, elderly person to wait during that time? Better spatial design and smoother processes can make a big difference.

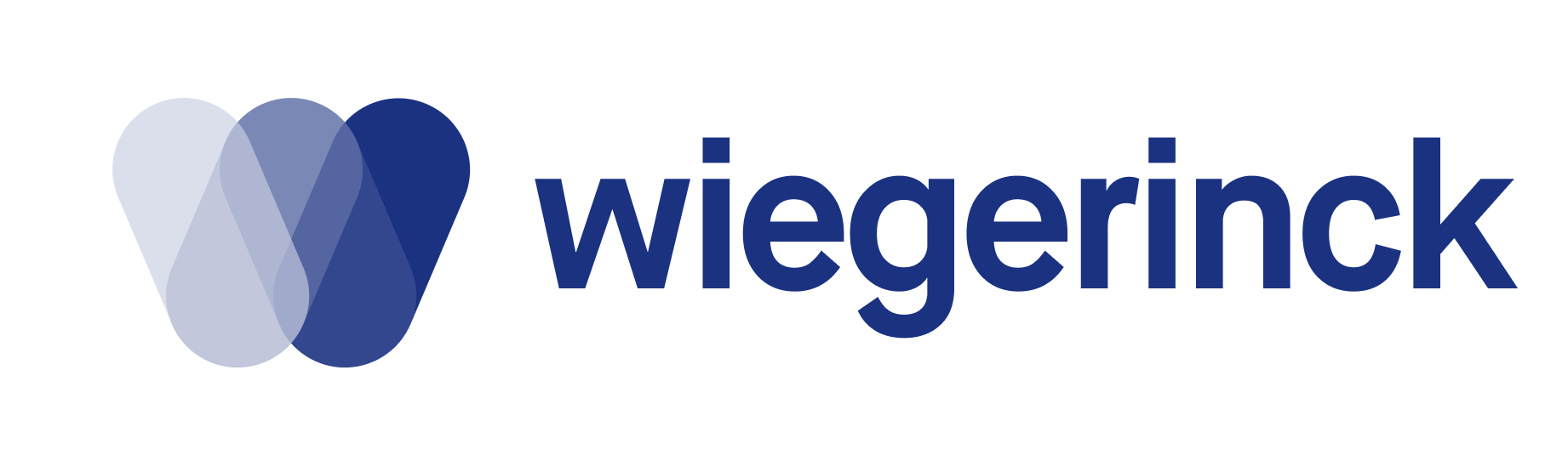

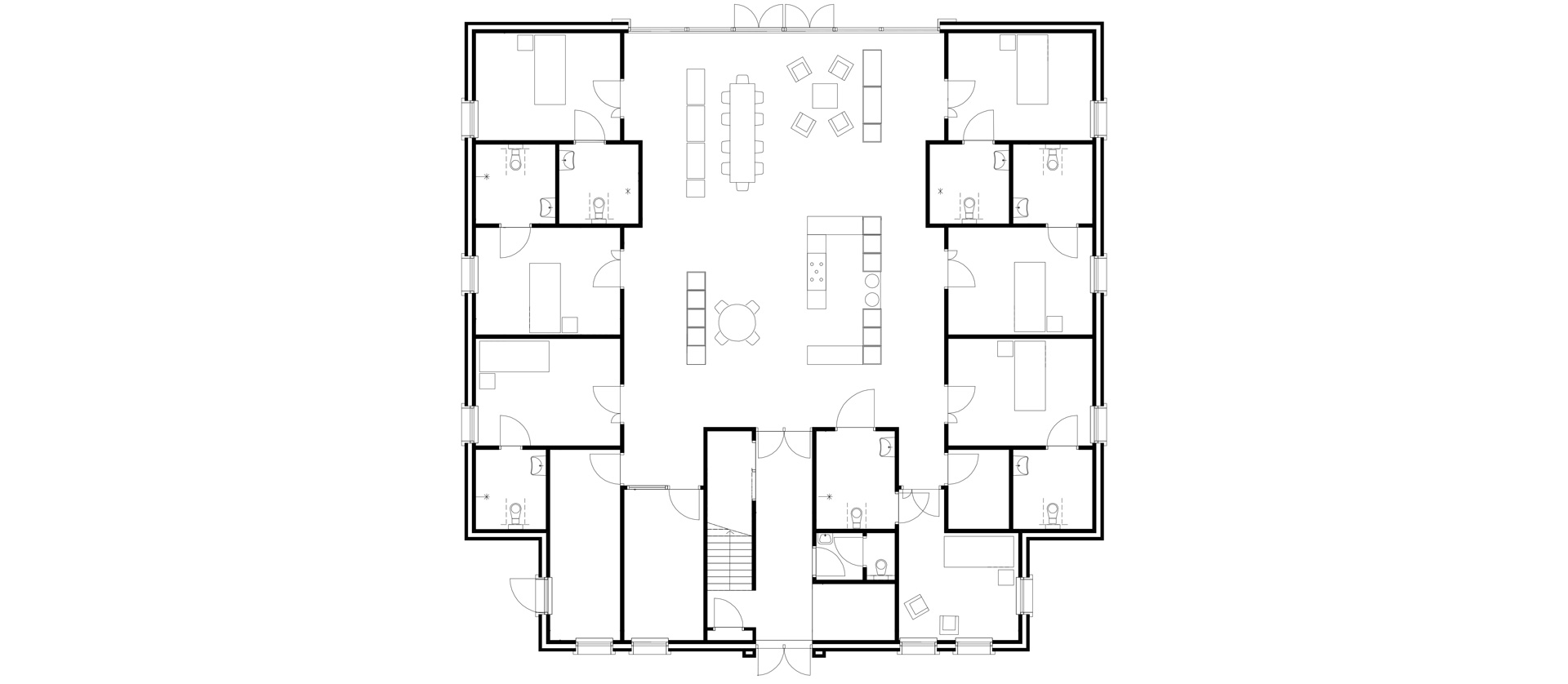

An active middle zone in a nursing ward where patients can reactivate under the watchful eye of care professionals.

Differentiate and vary

Whether using a walker or not, elderly people often keep their heads down when they walk and thus have a lower field of vision. Adapted signage can make it easier for them to navigate, and audio solutions for the very elderly are becoming increasingly available.

We also know that elderly people, especially those with dementia, have difficulty “reading” a room. Thus, in large hospital buildings, we need to focus on differentiating and varying spaces—in form, size and finish. Consider a clear distinction between a corridor and a waiting area. A pleasant, calming waiting area is a quiet, enclosed space that makes it clear to the user that he or she should stay put. The space is low in stimuli, with optimal acoustics and minimal passenger traffic. The “parking spaces” for wheelchairs, walkers and strollers are logically incorporated into the overall design. There are various seating areas for elderly patients and their companion(s), where they can talk quietly, read or watch TV.

Space gives peace of mind

Having a familiar face nearby reduces agitation and anxiety in elderly patients with dementia. This is another aspect that we should take into account. We should also make sure that in consultation and treatment rooms, there is enough room for the patient’s companion, usually a spouse or a family member, so that they can assist the patient with personal tasks, such as changing clothes. Another advantage is that the companion can listen in on the appointment and provide any additional information needed about the patient.

Decentralized stations provide good visibility of vulnerable patients.

Rapid deterioration

Older people admitted to the nursing ward often have a relatively long length of stay. In the hospital, elderly patients have the highest risk of functional decline. Every day, patients experience rapid deterioration of muscle mass, making recovery difficult and increasing the risk of falls. Oftentimes, hospitalization leads to a situation where they cannot safely return home.

Elderly patients who arrive at the hospital already very ill benefit most from low-stimulus single rooms with rooming-in options. After surgery or treatment, however, they recover best in an environment that encourages reactivation. An environment that operates more like a nursing home and encourages maximum exercise. There should be a comfortable chair in each room, where patients are encouraged to take their meals as soon as possible. As their recovery progresses, meals can be eaten together at tables. An open kitchen encourages movement because people can fetch their own drinks. And there should be plenty of places to sit and read, play a game, do a jigsaw puzzle or draw. Patients can gather in comfortable living rooms, where they can watch TV or receive visitors.

Starting points for a hospital design that meets the needs of elderly patients.

A good dose of green

In the reactivating nursing environment, common areas are spacious, but the bedrooms are quite compact. In other words, the bed regains its sleeping function, and outside the room there is plenty of space for activities and recovery. Depending on space and budget, these areas can include green indoor spaces, such as conservatories, patios and indoor gardens that are accessible all year round.

Seniors in the Nursing Home - Making Time for Care

New laws and regulations are aimed at ensuring that senior citizens are able to live at home for as long as possible. As a result, we are seeing a shift in nursing homes towards more intensive care for very elderly people (average age 85), often in the advanced stages of dementia or with a physical condition. For nursing home residents with care profiles VV4, VV5, VV6 and VV7, stays longer than four years are becoming less common.

Consequently, the vision for care is shifting as well. Care is less focused on rehabilitation and extending life and more on offering attention and improving quality of life, as residents spend the very last phase of their lives in the nursing home. We see family and loved ones looking for an environment where their loved one can live as happily and contentedly as possible.

Time for care and attention

Nursing home residents with advanced dementia can no longer perform normal daily activities. It was long thought that interior modifications, such as features that allow residents to locate their own apartments, could help. However, we now know that most of these measures have no real effect. In most cases, care workers have to accompany residents to and from their apartments. This example shows that we need to do everything possible to maximize time for real care so that care workers can do what they do best: provide direct care and personal attention to residents. Design solutions to support this goal are still in their infancy, but we at Wiegerinck are happy to join the conversation.

Good, healthy buildings are buildings that offer staff more time for providing care. Caregivers should have the time and energy to take a walk, play a game or chat with a resident. How can we work together to make this possible? For starters, we can make sure that the daily care tasks in residents’ apartments can be carried out as efficiently as possible. This means large bathrooms, where caregivers can assist residents without restriction and all the necessary equipment, such as a shower chair, is at hand. Other features include well-lit, spacious closets with easy access to (incontinence) materials and all other necessities, as well as convenient solutions for clean and soiled linen. By thinking and designing this way, we can ensure that tasks such as washing and dressing don’t take up more time than necessary, freeing up more time for meaningful activities.

At the 't Loug care homes in Delfzijl, apartments are situated directly around the living room.

Corridor or no corridor?

In group homes, it is important to keep lines of sight and walking routes as short as possible. Long corridors of apartments are not only challenging for residents (where’s my room again?) but also stress-inducing and tiring for employees. Internationally, there have been interesting developments with apartments situated around a central living room. When residents leave their apartments independently they immediately find themselves at the centre of domestic life. Meanwhile, care staff can easily keep an eye on each resident.

When we design a living room—regardless of its location—we create different areas so that the space is orderly and easy to read. Residents can participate in a joint activity or remain in a sheltered, quiet environment, where the brain can better process stimuli.

Eat well, enjoy more

In the living room, the kitchen has a central, important place. Staff spend quite a lot of time here: from breakfast to the final nightcap before bed. Meals are important, because, for seniors with dementia, eating and drinking are one of the few pleasures left to enjoy. So let’s make “food” an experience. Research shows that finger foods are often easier for elderly residents to handle themselves. Distractions at the table (looking at a fireplace, an aquarium, etc.) can also reduce boredom and prevent residents from leaving the table. It also helps to not put all residents together at one table. After all, not everyone likes that. Offering different dining options is a simple solution.

Presence versus absence

Due to all the laws and regulations, staff members do a lot of work at the computer. In addition, there are transfer moments and conversations with families and doctors. Throughout the industry, we are noticing a trend toward small, self-managing teams that work together and share necessary tasks. This is yet another effective way of creating more time and attention for residents.

A lot of work can also be carried out in the living room, where residents are visible and approachable. This means that the living room needs to be well-equipped with the proper health and safety features. And in cases where the living room is used by residents with (severe) dementia, we don’t need to worry about displaying privacy-sensitive information on screens. We need to think about how we can better balance presence/accessibility in a living room versus absence in an office.

Stimulating activity

Many nursing home residents struggle with boredom, which can often lead to poor sleep. Activities for residents are therefore essential. The more activities that can take place under staff supervision, the better. However, this is not always feasible or affordable. Therefore, we must design spaces so that residents are encouraged to engage in activities that they can still do themselves. A living room with different corners and places for various activities is a good start. When cabinets have closed doors, they can’t see that there are pencils, paper and puzzles inside. When all these things are visible, they are more inspired to take initiative themselves. Music and song appear to stimulate a deep response, even among those in the advanced stages of dementia. But is there a place where residents can sing or listen to music? Pets are another simple and relatively inexpensive source of activity.

The great outdoors

Ever since Florence Nightingale, we have known how important outdoor space is for people. Outside, all our senses are stimulated; we become alert and energized. Creating an equally attractive outdoor space for all nursing home residents with dementia remains a challenge. What we know is that the transition between inside and outside must be ‘soft’ so that elderly residents dare to venture outdoors by themselves without supervision. A veranda, for example, can be a good solution. It ensures that a comfortable outdoor space is available all year round, even when there is a lot of wind or sun.

Want to know more?

The ideas in this article are meant to excite and inspire: how do we give elderly people with dementia more self-direction in hospitals and nursing homes? How can we help care teams save time so that there is more time for meaningful activities? Wiegerinck is happy to share new ideas and solutions with you. If you would like to know more about our approach or exchange ideas about new design possibilities, feel free to give us a call.